In Part One of this two-part series, I shared the practical side of writing Buckskin Rides Again—how field notes became drafts, drafts became dispatches, and how a humble spreadsheet helped me chart not just the miles, but the map of the story’s meaning.

But systems can only take me so far. After organizing the miles, I had to face the mess no spreadsheet could fix: which truths I was willing to tell—and whom I might need to protect.

Writing about my family meant confronting the myths that shaped me. It meant noticing where my gaze lingered too long on one person, and where silence spoke volumes about another.

That’s the focus of Part Two: how I approached privacy, portrayal, and emotion with honesty while shaping real lives into story.

The memoirist stands as the reader’s only interpreter of what happened and why, which makes the work of revisiting and revising an act of responsibility as much as revelation. This is why doubt is baked into the memoir genre—between family recollections, between fact and feeling, even between drafts of ourselves.

Memoir is not an act of history but an act of memory, which is innately corrupt.

— Mary Karr, The Art of Memoir

Memoir and Mistrust

Novelists often say they had to invent a story to tell a deeper truth.

Memoirists use the inverse logic: we tell true stories to expose the fictions we’ve been living. And that’s why showing your personal growth is essential in memoir.

That was my experience writing Buckskin. Every so often, I’d check a memory with a family member—just to see how our recollections aligned. We’d usually agree on the basic facts, but not on what those facts meant. That’s why readers have to accept—but never fully trust—the memoirist’s role as interpreter.

Those gaps in recollection are the heartbeat of memoir. Here’s a small confession from Buckskin: my dad swears we owned so many station wagons that he can’t remember which one appears in half my stories. I went with the Vista Cruiser after he confirmed we’d owned at least one. But if he can’t recall whether a certain Ohio-to-California trip was in an Olds or a Buick—or whether it happened in 1972 or 1974—are you really going to miss the story for the footnotes? Does the make and color of the car matter in a story that isn’t about horsepower to begin with?

Come on.

The point of memoir is to put the reader inside the narrator’s lived experience—but that’s also the point of a novel. So if a writer can’t remember every fact or reconstruct every conversation verbatim, should they really call it memoir? Or should they write it as a novel instead?

I still ask myself that sometimes, especially when memory and evidence bump fists instead of shaking hands.

My bottom line: I wanted to stay within the form of memoir because I wanted to hold my feet to the fire of truth-telling.

Memoir isn’t the story of what happens, but of what we think happened, and what that means.

— Abigail Thomas, A Three Dog Life

Memoir-Truth Isn’t The Whole Truth

I wish I could give credit to the first person who said this, but that won’t stop me from repeating it: memoir is just like life, but it excludes the boring stuff. This is how I approached Buckskin.

If you want to include every detail—the errands, the emails, the filler between turning points—you should write your autobiography (or hire a ghostwriter to do it for you). As Gore Vidal said in his memoir, Palimpsest, “A memoir is how one remembers one’s own life, while an autobiography is history, requiring research, dates, facts, double-checked.”

That doesn’t mean a memoir can go rogue from reality. When it came to verifiable details—dates, locations, historical context—I fact-checked them. The emotions could be subjective, but the story’s scaffolding needed to be sound.

Memoir should be based in fact, but it leans on the tools of fiction to make it a pleasurable read. Those tools include character arcs, flashbacks, rising tension, themes, and so on.

I wrote a number of anecdotes and memories that didn’t make the final cut. I knew they wouldn’t when I wrote them, but I had to move them out of my head—out of the way—so I could tell the stories that were more apropos. They were scaffolding, never intended to remain intact. I think writers have to give themselves this kind of support. It’s part of my Write-First philosophy.1

To keep myself honest on the page, I adopted a few rules of thumb:

I never gave both first and last names, but if I changed a name, I declared it.

I never published faces of characters besides myself unless they were from at least 30 years ago.

I kept reminding myself if I shared family lore/gossip I had to frame it in terms of what it said about my growth/development, the then-me versus the now-me and to explore the whys behind my beliefs. Memoir is the writer’s journey.

There were times when I thought readers might “want” to know a story or a character detail, but that detail didn’t move the story ahead, so I left it off the page. I’ll talk about this later in “The Tenderness Test.”

Writers like Suleika Jaouad made different but equally valid choices—compressing timelines or adjusting backstories to protect privacy and to serve narrative shape. In Between Two Kingdoms, for example, she altered details about her first partner’s life and changed his name, a decision that drew curiosity from readers and book clubs (including mine).

Her approach underscores how flexible the genre can be. I chose a different path. I didn’t use composite characters or alter biographies; I stayed anchored in lived truth, even when it made the story messier. Every memoirist has to find that balance between emotional truth and narrative clarity—between compassion and precision.

The Tenderness Test

Every memoirist eventually reaches a moment when truth and tenderness collide. You write something raw—something you know is real—and then you have to ask: Does telling this serve the story, or just satisfy me?

There’s no easy answer. Writing honestly doesn’t mean writing mercilessly. The art lies in knowing when to press forward and when to pause. Sometimes the kindest thing a writer can do—for others and for herself—is to stop.

Suleika Jaouad tells a story that captures this perfectly. In an interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, she discussed a choice she made in Between Two Kingdoms:

“At some point in the process, I started sending sections to my friend and mentor, the brilliant writer Melissa Febos. One was a 60-page chapter that I found excruciating to write because I was worried it might be hurtful to someone in my life. I told Melissa this, and she said, ‘If you’re going to include it, you have to have a conversation with them. But in the meantime, keep writing.’ When I got to the end, just before the complete manuscript was due, Melissa asked me if I’d had that tough conversation. I told her I hadn’t been able to. Her response was straightforward. She said, ‘Then cut it.’”

That exchange holds the essence of what I think of as the tenderness test: keep writing, keep feeling, but if you can’t yet tell a story responsibly, set it aside. (This good life advice, folks).

Sometimes restraint is the truest form of integrity. I’ve had my own versions of Jaouad’s decision—chapters I drafted but couldn’t yet stand behind.

Thanks for reading Part Two. I’m eager to hear how you navigate truth, tenderness, and trust in your own storytelling. Will you let me know? There’s no wrong answer—only different moral compasses.

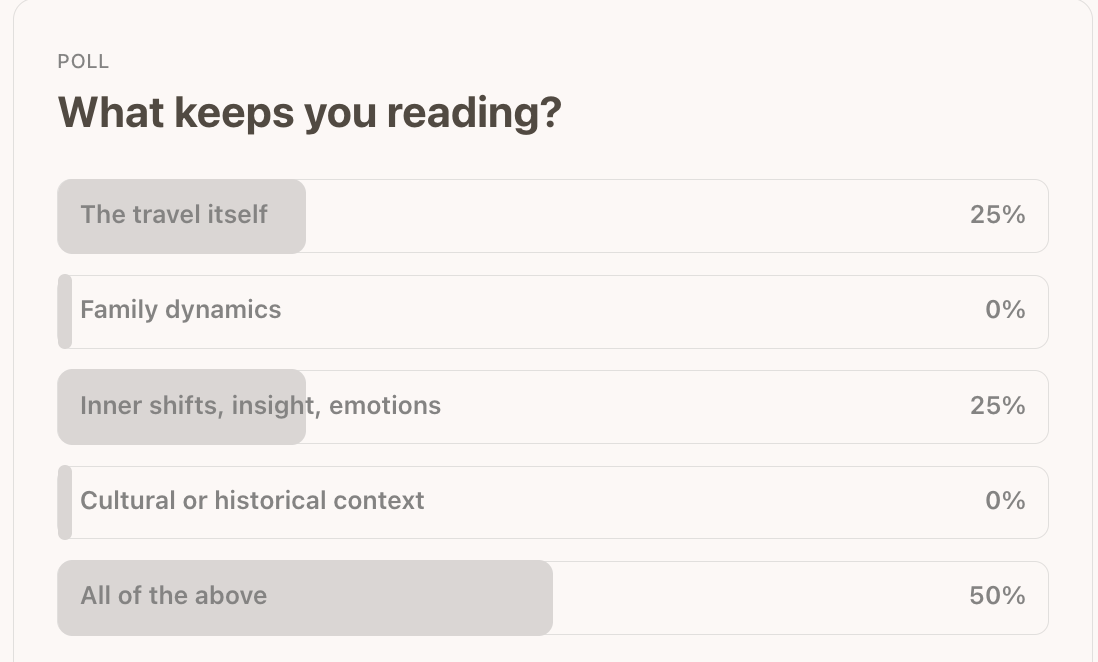

Part One Poll Results. Thanks to those who participated. I heard directly from a couple of you.

The Write-First Philosophy is to write-write-write with out editing. Get the words, stories, emotions flowing first. Editing comes later.