While traveling in Paducah, Kentucky, I encountered the legacy of an historical character that I can’t get out of my head. Here’s a video about Maggie Stead, a woman who, at the age of 26, decided Paducah needed a hotel for Black performers on the “Chitlin Circuit”and Negro League baseball players.

When I can’t get someone or something out of my mind, I write about it, in this case I created a fictional Maggie Stead named Cassie, toiling away in her hotel kitchen on a July afternoon. Here’s a couple of my opening paragraphs:

Cassie’s inner clock kept time within five minutes of reality. In no more than seven of them, she’d serve dinner for sixteen members of the St. Louis Stars baseball team on long tables under the eating pavilion she’d been able to build after a successful summer of hosting Negro League teams in 1905.

With rivulets running down her back and throbbing feet, she stood at the kitchen window slicing Cherokee Purples watching the men jibe and banter as they waited for their meal, wondering how much cooler their gray flannel travel jerseys and simple trousers might feel. She’d been thinking of sewing herself a couple of split skirts like Annie Oakley’s. Oh, to be rid of petticoats!

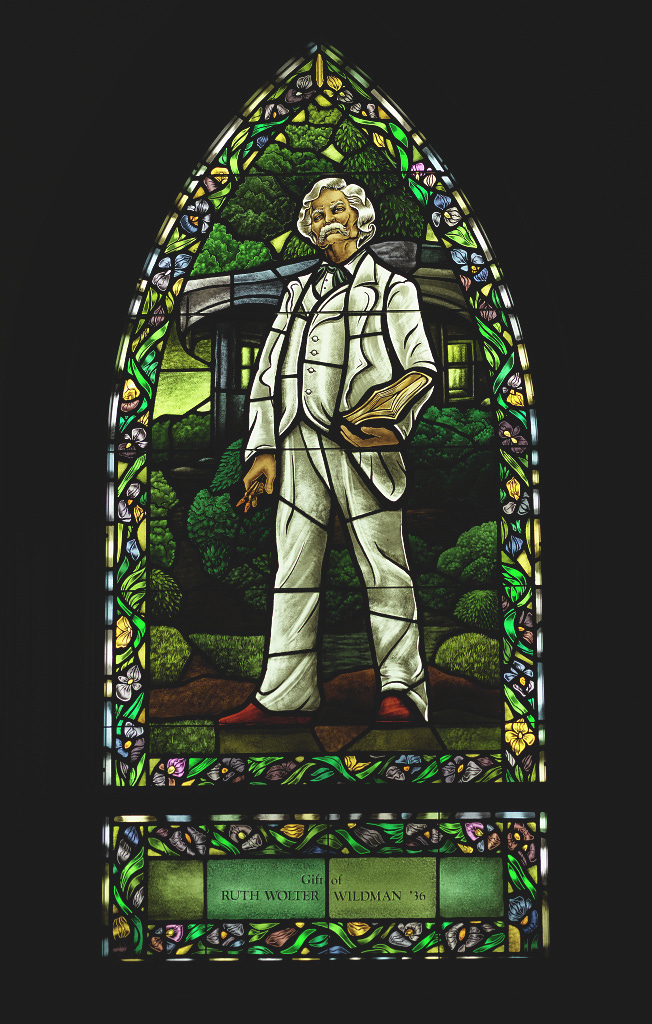

Next, I fed my draft to Living Writer’s artificial intelligence (AI) tool, asking it to rewrite my work in the voice of Mark Twain. It gave me:

Cassie's innards were wound tighter than a new spring on a pocket watch, always keeping her within a stone's throw of the true time. And she wagered, not seven minutes more would pass before she was to lay out the victuals for the sixteen men of the St. Louis Stars—a baseball team of some local renown—right under the feasting shelter she hammered together after a banner season hosting those Negro League outfits back in '05.

With sweat streaming like the Mississippi down her spine and her dogs barking louder than a coonhound at a full moon, there she was at the kitchen pane, slicing up Cherokee Purples whilst casting a glance towards the boys outside, jesting and sparring in their patient hunger. She envied them their cool drapery—their gray flannels and plain britches—and it set her to ponderin' on fashioning herself a pair of split skirts, something like what Annie Oakley'd wear—anything to escape the tyranny of petticoats.

WOW, I was stunned.

Then I wondered what it might look like in William Faulkner’s voice and got this:

In the waning hours when her internal horologe had near about synchronized itself with the immutable march of time's own passage, Cassandra prepared feasttime for the amassed congregation of St. Louis' own ball players, those stars bereft of the firmament aligned under her timber shelter, a monument borne of the year of grace 1905. Beads of perspiration traversed the planes of her back beneath folds of fabric, whilst her feet bore a pulsating testament to labor. Cassandra, a sentinel by the windowpane in her privy grot, etched incarnadine crescents of Cherokee heirlooms, peering intently at the spectacle of jibes and such banter lofted 'twixt men in anticipation of repast, pondering the blessed chill of their garb, cut in the manner so unaffected, of gray flannel and pantaloon, so unlike her own yoke of petticoats.

And upon such thoughts, she entertained whimsy of forswearing all and crafting for oneself a damsel's bifurcated garment, emulating pristine Oakley, maverick of the Wild West Show—oh! a freedom like none other it would be, depriving earth of its petticoats.

Faulker’s version sounded true to the era, but it’s not right for this story and not the kind of book I enjoy. I ran it through a couple of other iterations asking for different stylistic rewrites and Twain’s was the hands-down winner.

If you’re starting to feel squeamish about writers using AI, take a deep breath while we explore the technology’s current and coming impact on writing and publishing.

We must talk about artificial intelligence (AI)

We’ve been using artificial intelligence for a long while, friends. Remember that annoying jumping paper clip, Clippit, that kept popping up in the corner of our Word files starting in 2000? Well, we’ve come a long way in a short time.

When I showed my Mark Twain AI experiment to my longtime writing buddy, Anne, she asked three questions I think we’re all asking. I’ll take them in turn.

Q: Is it unethical or what?

A: Technology moves faster than our human ability to regulate every new feature and application. Publishers, academic institutions, and other interested parties are forming ethical standards—along with disclosure requirements and other guidelines—for writers using artificial intelligence. The Author’s Guild is my go-to authority and if my story about Cassie ever gets past my own hard drive, I’ll follow the Guild’s current guidelines, and those of my agent and publisher, for disclosing how I used AI.

Writing is a collaborative act and we always get input (often unbidden). If AI puts your blood pressure up, perhaps ask yourself if what I’ve done with the Living Writer program is any different from asking my friend Anne to suggest a way to spiff up the narration. Even Mark Twain asked friends, family, and servants to help him improve his drafts.

In this instance, I’ve used a tool instead of humans. I see no ethical breach in collaborating with either humans or AI tools if it’s de minimus.

Q: Will I use any of it?

A: Twain had a couple of lines of dialogue that I thought were more realistic for the era than mine. and I’ll use them. For example, I originally wrote this line when Cassie mistook two players with jazzy nicknames. I said: “The first baseman there's Boom-Boom. I'm Baby Cakes.”

I prefer the Twain version. “That over yonder’s Boom-Boom. I answer to Baby Cakes.”

As much as I admire Twain’s prose overall, I prefer my own narrative style for Cassie’s story. To my ear, his version is more masculine—do you feel that way about it? Please give me your analysis of the AI Twain version.

Q: Oh my God, why bother being a writer anymore with that out there?

A: I can’t wallow in this kind of thinking because we can’t stop the march of innovation. I learned to drive a stick shift, but now transmissions are automatic—I had nothing to do with that transition but now that it’s here I need to go along. My focus is to be the best driver—and storyteller—I can be. I must accept that there will be bad actors in the writing and publishing business while keeping my nose clean. And on that note, there are bad actors in every industry already.

If I stop writing because there’s a possibility that SOME DAY a machine will write a better story than I can, I’ll have only myself to blame for my ensuing misery. Writers write. Storytellers tell stories. We do it as much to scratch our creative itches as to entertain and inform our readers.

I hope you’d like to talk about this. If so, please leave a civil comment or question and I’ll do my best to point you to resources I know and trust on these AI issues.

Before I leave you, did you know Mark Twain’s Elmira octagonal study was recently restored? I was there in 2018.

The name inscribed on the planter is Clara L. Clemens, Twain’s only surviving child. His octagonal study is behind me.