Need to catch up? Here’s what you missed.

On the third day of my travels, heading west toward Little Rock, I stopped at a Mississippi Cracker Barrel. I've got my order down pat—greens, pintos, cornbread, half-sweet tea—so I rattled it off as soon as the server arrived.

She was a petite woman about my age. When she brought my food, she noticed my full-face helmet on the seat beside me. “Isn’t that hot?” she asked, fanning herself. “Back in Texas, we don’t have helmet laws. I love the wind in my face.”

I feel naked just riding out of the garage without a helmet, but many American riders skip them, and if they are required by law, will opt for styles that leave the face exposed—right where most impact injuries happen. It’s dangerous, but I don’t argue—this country’s got enough friction. I just said, “I dunno. As long as I’m moving, I get enough air flow. If I’m in a construction zone, I lift the front.”

I flipped up the helmet to show her how it opened from the bottom to reveal my face. She nodded. “Never seen one like that.”

The road has a way of revealing kinship—shared language, unspoken codes, a flash of belonging you didn’t know you were missing. It took me back to my first identity on the road: Buckskin.

Handle: Buckskin

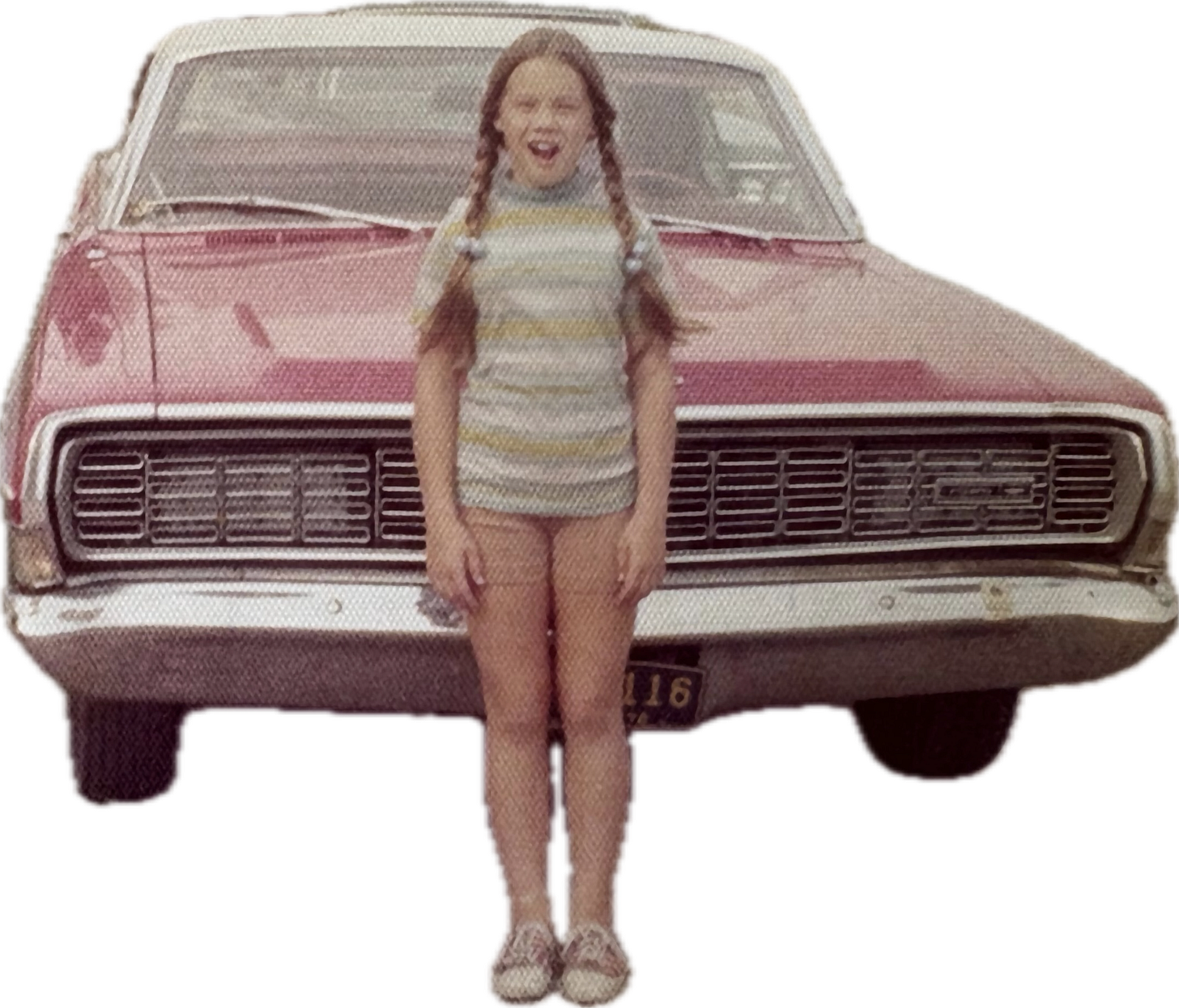

Before I became a solo motorcyclist, I was a kid with a CB handle, wedged into the way-back of a Vista Cruiser station wagon. Every other summer, we drove from Ohio to California to visit Dad’s family—4,400 miles round trip squeezed into a two-week vacation. To minimize motel stops, Mom and Dad folded the back seats down and installed a mattress.

We’d head out after dinner, fall asleep near Indianapolis, and wake up crossing the Mississippi. Traveling at night was a genius way to minimize the bickering and bathroom breaks, but that was just one of many travel hacks my parents perfected.

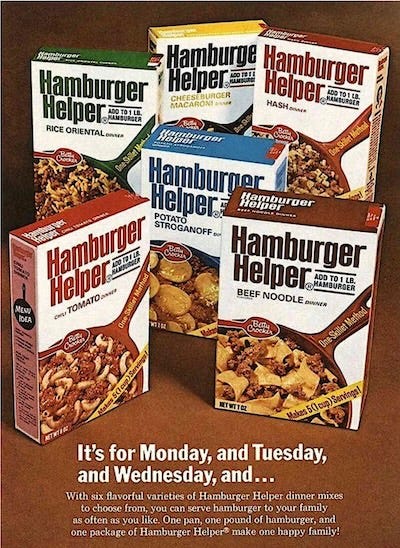

When we finally stopped at a motel—usually in west Texas or New Mexico—Dad took us kids to the swimming pool, where we worked off our back-seat leg cramps while Mom whipped up some Hamburger Helper in the electric frying pan that she’d packed in the storage compartment beneath the mattress.

In the morning, we’d choose our favorite sugary cereal from a multi-pack of single-serving boxes. They were a marvel in package design, cleverly perforated so that the box doubled as a cereal bowl. Dad actually liked the dreaded Raisin Bran, so it worked out to everyone’s satisfaction.

The CB radio kept us entertained and informed—of road hazards, speed traps, construction delays—and we adopted its culture with gusto. Our favorite song, “Convoy,” played in a loop on AM radio, and no one said “okay” when they could say “10-4.”

I was Buckskin. Dad was Stagecoach. Mom was Running Deer. My brother and sister, three and five years younger, had CB handles too, but I don’t remember theirs—or if they ever grabbed the handset.

One night, riding shotgun while Stagecoach drove, he pointed out a patrol car tucked behind a billboard. “Hey Buckskin, wanna report the bear?”

I did. “Breaker 1-9, this is Buckskin. We spot a smokey behind the Coppertone sign.”

A voice came back, raspy and amused: “Breaker 1-9. Got a directional and a mile marker there, Buckskin?”

I didn’t, so Stagecoach fed me the lines. Upon my warning, CB operators immediately conformed to the speed limit, leaving the uninformed drivers to be swept up by law enforcement. It thrilled me to shift the flow of traffic with a few crackly words.

The power of broadcasting!

Wobbling in the Wind

By late afternoon, approaching Memphis, the winds promised in the forecast picked up and rode alongside me, sometimes playful, often pushing. Just a week before, a series of tornadoes had struck Arkansas and one sent debris 30,000 feet into the sky—planes fly at that altitude. You don’t fully realize the impact of wind when you’re encased in a vehicle, but it’s inescapable from the saddle of a motorcycle.

Somewhere between Memphis and Little Rock, a truck pulling a camper trailer wobbled several times. I was genuinely concerned it might jackknife and cause a mass incident. I’d seen it happen before, so I throttled down and followed at a distance.

That’s a familiar stance—easing off when things threaten to spin out. I started doing it at home by the time I was five. My siblings, close in age, were messy, loud, argumentative, and unpredictable—they’ll even admit that today—and it wore on Mom's nerves. Duh, of course it did.

Dad wasn’t much for domestic tangles. It was Mom who kept the temperature in the house—and she often ran hot.

Eldest daughters back then were often conscripted as junior mothers: “Get in there and break that up…” Plenty of people are wired for bossiness, and some junior mothers grew into responsible roles in society. This does not describe me.

I arranged my own after-school play dates with neighborhood friends pretty young. This sounds sophisticated, but it was kinda like, “Hey, can we play?”

Barring that, I always had my books, which I’d learned to sight-read before first grade. I grabbed one, along with a flashlight, and read in a closet—which had the side benefit of shutting out the chaos. When someone found me reading, how could they be angry?

Reading sharpened my ear for tone, contradiction, and intent—skills I would come to rely on as a lifelong observer. I learned early to stay quiet when adults were talking, easing into the edges of living rooms like a junior anthropologist. I didn’t want them to know I was there—they’d surely shoo me out. Little pitchers have big ears, as the saying goes. I once sat behind Papaw’s naugahyde recliner, invisible but close enough to catch the scent of Old Spice and hear every word.

Remember when I said I’d choose invisibility as a superpower (Dispatch #1)—not to disappear, but to see the world unfiltered? This is where it started.

Adult conversations were sometimes about family, but just as often they were about the world unraveling around us: assassinations, war, Kent State. My silence let me track the difference between what adults told each other—and what they tried to pass off to kids. The tones that shifted mid-sentence. The coded language. The awkward pauses that carried the real message.

I didn’t have language for it yet. But that dual exposure—slipping between the kid world and the adult one—laid bare the moments when I was being managed. And I hated it—especially when I knew the larger truth. I wanted clarity—to know where I stood. And from a young age, I started looking for it myself.

I didn’t know it back then, squeezed into the Vista Cruiser, but I was developing a new kind of awareness—not just reading the road or the weather, but sensing what was surfacing inside of me, and all around me. Being Buckskin was how I moved through the world. It still is.

She Needed to Believe. I Needed to Question

Now, all these years later, Buckskin is back in the saddle—but this time, I’m listening for something quieter. Something just beneath the engine noise and wind. Listening to memory—and its absences—when it comes to my mother.

Back at home, she was the show director while Dad ran the lights. They took turns at the wheel on the road, but riding shotgun with Stagecoach was the precious counterpoint to life at home. I never stepped up to ride shotgun with Running Deer.

Mom’s first priority was safety. She sometimes bent the truth to keep us from making stupid choices. But from my spot in the wings, I caught the wider view. Once I saw the seams in Mom’s version of the world, I couldn’t unsee them.

If I pointed out a contradiction, she was quick: “Don’t talk back,” she’d say. I wasn’t talking back—I was thinking forward. Out loud. Maybe that’s where the wedge began: not with rebellion, but with divergence.

She needed belief to feel safe. I needed inquiry to feel sane.

We’d long been traveling the same road, but from the very start, we were riding in different directions.

Later, I came to see a different kind of strength in my mother—not built on questioning, but on holding fast to what she believed. She didn’t need all the facts to take a stand. If something struck her as dangerous or unjust, she latched on with everything she had. She was slow to trust what seemed too polished, too perfect—but she could fall hard for a big promise if it looked like a way to some help or get ahead.

Her certainty was her compass—burning away doubts and unwanted contradictions.

I was too callow to understand what the late ’60s had done to people like her—how fast the ground moved, how loud the voices grew. Certainty gave her something to stand on.

What I took for inflexibility may have been her shield.

It took me decades to recognize that.

She had her handle. I had mine.

We traveled the same highways, but never side by side.

With this ride, I began to bring Running Deer back into the frame.

Not for her sake.

For mine.

Attention writers: Download craft tips and memoir prompts based on this dispatch.

🚦 Ahead on the road:

In Hot Springs, Arkansas, a soak at the historic Buckstaff bathhouse becomes a portal to generational memory.

![[Dispatch #1] Slow Travel, Fast Truths](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6EOi!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F70249fd4-2609-4f8d-b983-c386ffdd41eb_3024x4032.jpeg)

Share this post